Learning CUDA by optimizing matrix-vector multiplication (SGEMV) for cuBLAS-like performance - A worklog

Matrix-vector multiplication is a foundational operation in linear algebra, where a matrix transforms an input vector into an output vector. This operation basically powers numerous fields including computer science and deep learning. Optimizing matrix-vector multiplication, especially in the context of GPU programming and CUDA can help us learn many new things.

In this worklog, we will start by benchmarking cuBLAS's matrix-vector multiplication performance then we will iteratively optimize it in CUDA to see how close we can get to cuBLAS. The intention is to not replace it, but to learn from it. The NVIDIA GPU used for this worklog is one GTX 1050Ti (that's all I have got right now). By the end of this worklog, we will achieve what the following figure shows:

The full code is available on the GitHub repository: Optimizing SGEMV in CUDA

If you want me to work together with you on deep learning models, inference, training, software development, custom CUDA kernels or something else then you can shoot a direct message (DM) to me here: me on X (formerly Twitter)

Let's start!

Some background first

From now on, we will call matrix-vector multiplication as SGEMV which stands for Single-Precision General Matrix-Vector multiplication. The breakdown of this term is:

- S: Indicates single-precision (-bit floating-point numbers).

- GE: Refers to a general matrix, meaning the matrix can have any shape or content (not restricted to special forms like symmetric or diagonal matrices).

- MV: Stands for matrix-vector multiplication, the core operation the function performs.

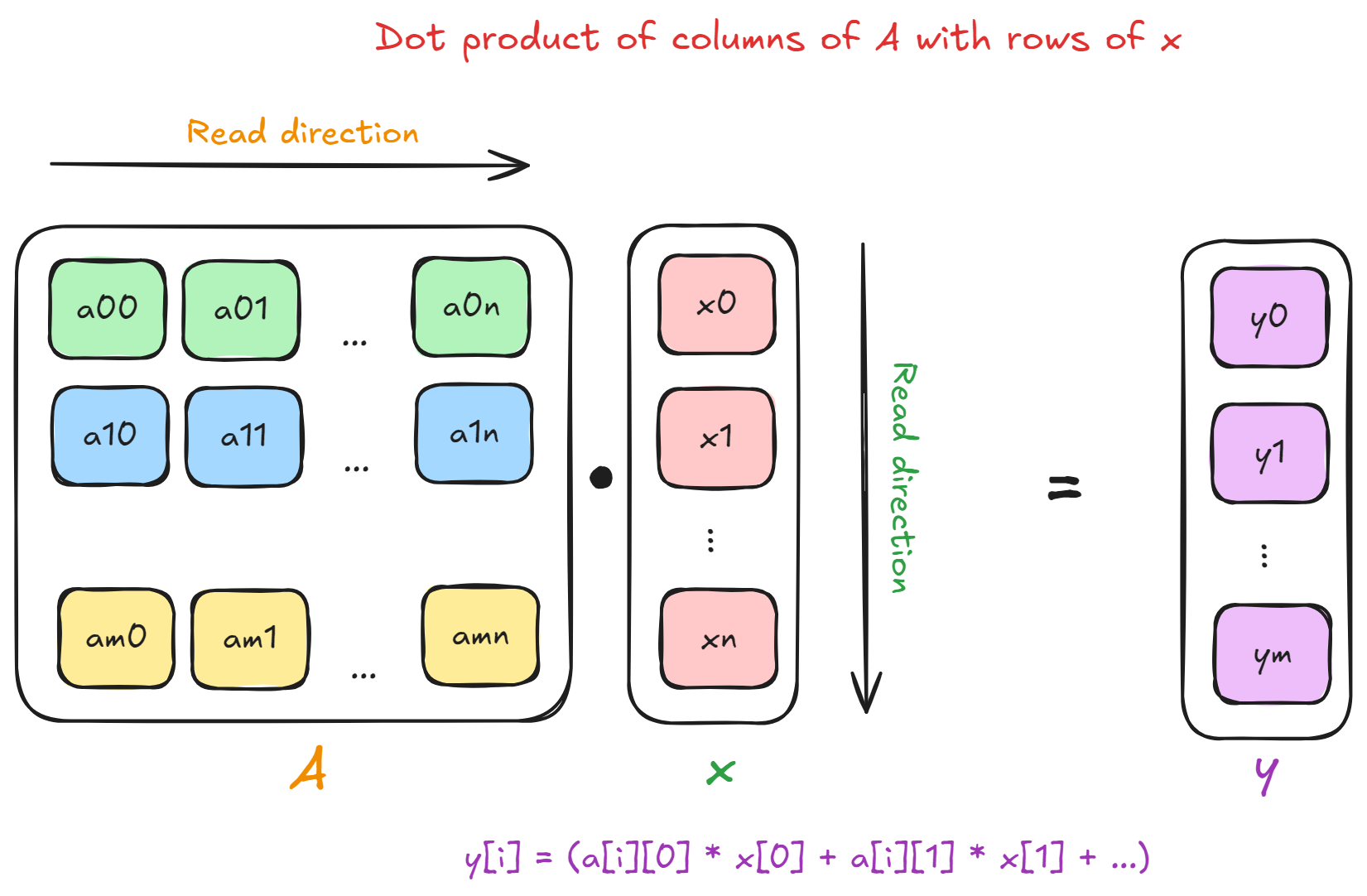

In essence, given a matrix of shape and an input vector of shape , SGEMV computes an output vector given as:

Here the terms and are some scalar coefficients (floating point numbers). In this worklog, we will assume the following for simplicity:

- The shape of the matrix will be

- The shape of the vector will be

- The scalars and

And that leaves us with:

The figure above and the pseudocode below shows this computation. Note that each row of the matrix performs a dot product with the entire input vector to compute one element of the output vector .

function sgemv_basic(A, x, y, M, N) {

// Initialize output vector

for (i = 0; i < M; i++) {

y[i] = 0;

}

// Perform the computation

for (i = 0; i < M; i++) {

for (j = 0; j < N; j++) {

y[i] += A[i][j] * x[j];

}

}

}

Memory-bound tasks and FLOPS

This section is very important in terms of comparing performance characteristics of operations like matrix-vector multiplication (SGEMV) and matrix-matrix multiplication (SGEMM). First, we need to define the words FLOPs (notice the small 's') and FLOPS.

Basically:

- FLOPs stands for the total number of floating-point operations performed in a computation. The operation can be anything like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and so on.

- FLOPS measures the rate of floating-point operations that a system can perform in one second. If the system performs FLOPs in seconds then FLOPS is given by . Also, GFLOPS = FLOPS.

Now, even though matrix-vector multiplication can be thought of as a special case of matrix-matrix multiplication, there are some differences when it comes to measuring performance of both the operations in CUDA.

SGEMV is a memory-bound operation whereas, SGEMM is a compute-bound operation. Let's calculate the FLOPs required for both of these operations:

Matrix-vector (SGEMV)

- Multiplies a matrix with a vector resulting in a vector .

- Memory accesses:

- Reads ( elements)

- Reads ( elements)

- Writes ( elements)

- Computations:

- Each row of is multiplied with , resulting in dot products.

- Each dot product consists of multiplications and additions.

- FLOPs:

- floating-point number is bytes.

- Bytes transferred:

Matrix-matrix (SGEMM)

- Multiplies two matrices and resulting in a matrix .

- Memory accesses:

- Reads ( elements)

- Reads ( elements)

- Writes ( elements)

- Computations:

- Dot product of row of with column of

- Each dot product consists of multiplications and additions.

- FLOPs:

- floating-point number is bytes.

- Bytes transferred:

We divide the FLOPs by the total bytes transferred to calculate the computational intensity of the operation.

Considering , and , for SGEMV we get:

and for SGEMM, we get:

As we can see, the computational intensity for SGEMV is very low compared to SGEMM i.e. more time is spent transferring the data from (and to) the global memory of the GPU compared to the actual computation time. Conversly, for SGEMM more time is spent doing the actual computation than transferring the data from (and to) the global memory.

Thus, SGEMV is a memory-bound operation. So, we need to make sure that we are maximizing the memory bandwidth that our CUDA kernel achieves, such that it is close to the maximum memory bandwidth of the GPU ( GB/s in our case).

Benchmark - cuBLAS implementation

Let's benchmark the SGEMV implementation that cuBLAS provides. To do this, we simply use the cublasSgemv function. Below is the corresponding code snippet that does this:

cublasHandle_t handle;

cublasCreate(&handle);

float alpha = 1.0f, beta = 0.0f;

cublasSgemv(

handle, CUBLAS_OP_T, N, M,

&alpha, matd, N, vecd,

1, &beta, resd, 1

);

The on-device matrix is defined as matd, input vector is defined as vecd, and the resulting vector is defined as resd.

The matrix matd is stored in the row-major layout in memory and we will use linear indices to access its elements. When we run this we get:

>> GPU allocation time: 5.698560 ms

>> Host to device transfer time: 23.588863 ms

------- cuBLAS sgmev kernel ---------

>> Execution time: 1.532928 ms

>> Achieved (GFLOPS): 43.778225

>> Theoretical max (GFLOPS): 1911.040039

>> Maximum memory bandwidth: 112.127998 GB/s

>> Achieves 2.290806 % of peak GFLOPS

>> Achieves 78.114754 % of peak Memory Bandwidth

---------------------------

>> Device to host transfer time: 0.042816 ms

As expected, we see that the FLOPS achieved is GFLOPS i.e. much less than the theoretical maximum which the GPU can achieve. But, cuBLAS achieves around % of the peak memory bandwidth which is great for SGEMV since it is a memory-bound operation, as seen above.

Let's first write a naive kernel in CUDA for SGMEV and iteratively improve it.

Kernel 1 - Naive SGEMV

Following the figure above, we can write a naive kernel for SGEMV. Each thread in a thread block will compute one output element of the vector resd in this kernel. The index of the current row and the corresponding output element will be written as row = blockDim.x * blockIdx.x + threadIdx.x.

The corresponding code snippet for this kernel looks like:

int row = blockDim.x * blockIdx.x + threadIdx.x;

if (row < M) {

float sum = 0.0f;

for (int col = 0; col < N; col++) {

sum += matd[row * N + col] * vecd[col];

}

resd[row] = sum;

}

Running this kernel results in:

>> GPU allocation time: 5.820416 ms

>> Host to device transfer time: 24.071072 ms

------- Naive sgmev kernel ---------

>> Execution time: 8.279040 ms

>> Achieved (GFLOPS): 8.105875

>> Theoretical max (GFLOPS): 1911.040039

>> Maximum memory bandwidth: 112.127998 GB/s

>> Achieves 0.424160 % of peak GFLOPS

>> Achieves 14.463547 % of peak Memory Bandwidth

---------------------------

>> Device to host transfer time: 0.048992 ms

The naive kernel achieves only GFLOPS which is around % of the peak GFLOPS. Apart from that, it achieves only % of the peak memory bandwidth. This result is kind of unimpressive.

But no worries, we can improve this!

Kernel 2 - Coalesced access with reductions

One way to improve the naive kernel is to ensure that the memory accesses to both the matrix matd and vector vecd are coalesced. Let's understand what that means.

In CUDA, we have a grid of blocks where each block can have number of threads. The streaming multiprocessors (SM) on the GPU process each block in a 'group' of threads. This group of threads is called a warp. In essence, the SM can execute one instruction at a time for all the threads in a warp. Thus, each block consists of warps.

But what does this have to do with memory accesses? Well, let's see how the memory accesses for the matrix matd looks like in the naive kernel.

Warp 1 (Threads 0-31):

Assuming that we are dealing with the first block where blockIdx.x = 0, the number of threads in a block is , and all the threads in this warp of block will execute one instruction in parallel, then we have:

Thread executing:

- The value of

row= = - Thread will enter the for loop now.

- We have

col= for this thread in the start - Element of

matdaccessed = =

Now, at the same time, we have:

Thread executing:

- The value of

row= = - Thread will enter the for loop now.

- We have

col= for this thread in the start - Element of

matdaccessed = =

Similary, we can see that for this particular warp the elements of the matrix matd accessed by the other threads will be always separated by elements. But, this is actually NOT an optimal way to access data residing in the global memory! We need to access data from the global memory in a coalesced manner.

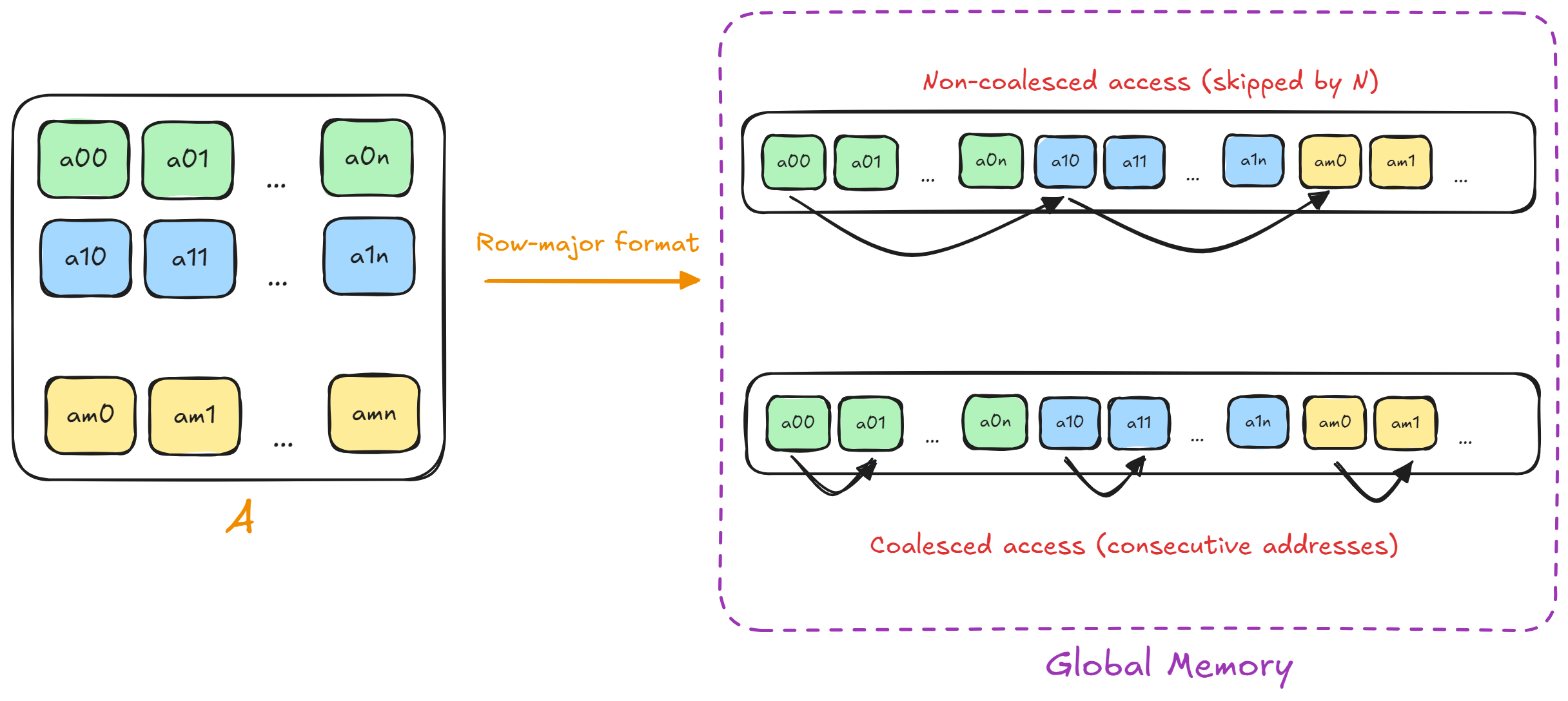

Coalesced memory access occurs when threads in a warp ( threads) access consecutive memory addresses, allowing the 'memory controller' to combine these accesses into a single memory transaction. Global memory on GPUs has high latency and limited bandwidth compared to the speed of computation. Coalescing memory accesses minimizes the number of transactions required to fetch data, maximizing the effective bandwidth. Also, the hardware is designed to handle these coalesced accesses efficiently. When the accesses to the global memory are scattered or random, it forces the 'memory controller' to dispatch multiple memory transactions. This results in a slowdown compared to when the memory accesses are coalesced.

The matrix matd is stored in row-major format in the global memory i.e. the elements of the matrix in each row are next to each other (in consecutive memory addresses). The figure below shows the difference of coalesced vs. non-coalesced accesses in the matrix.

In this kernel, each block will operate on one row of the matrix. Also, we will assume that each block contains of only threads i.e. warp. Consecutive threads in the warp will load consecutive elements in the row of the matrix matd and the vector vecd. We will also have a private variable (private to each thread in a warp) called partial_sum which will hold the partial sum of the elements processed by one particular thread. The below code snippet shows this:

int bid = blockIdx.x;

if (bid >= M) return;

int tid = threadIdx.x;

// each thread calculates its own partial output

float partial_sum = 0.f;

for (int col = tid; col < N; col += blockDim.x) {

partial_sum += matd[bid * N + col] * vecd[col];

}

For example, if bid = 0 and blockDim.x = 32 then a thread with index tid in this block will process the elements tid, tid + blockDim.x, tid + 2 * blockDim.x and so on. Thread processes the elements , , etc... thread processes the elements , , etc... and the same for remaining threads i.e. consecutive elements are loaded and processed by each thread which results in coalesced global memory access.

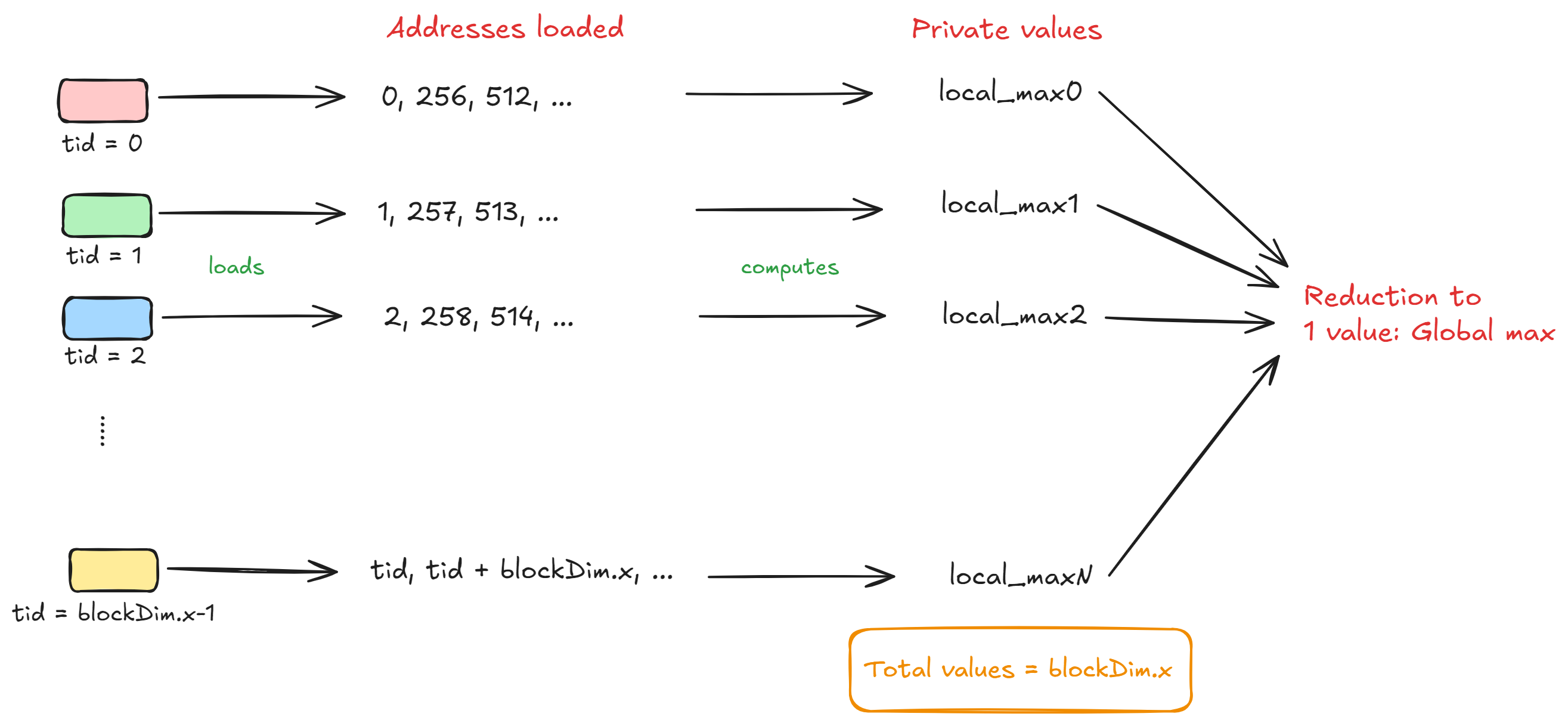

But, there's a problem! Each thread will have its own partial_sum variable. To have the final dot product, we need to sum the partial sums for all the threads that are present in the warp. Note that the final value of the dot product of two vectors is a single floating-point number.

This is where reductions can help us. We can essentially 'communicate' values between the threads present in a block/warp using shared memory or warp shuffle intrinsics, because every thread in a block/warp can have access to the block's shared memory. Have a look at my CUDA softmax worklog which dives deeper into reductions. The figure below can help you understand reduction for finding the maximum value:

So, the final value of the dot product will be a sum reduction on the partial_sum variable for all the threads that are present within the warp. The utility function warpReduceSum will help us sum up all the partial sums that are calculated by the threads. Finally, we write the result into the corresponding index of the output vector:

// warp-level sum reduction

float sum = warpReduceSum(partial_sum);

// only first thread writes the output to global memory

if (tid == 0) {

resd[bid] = sum;

}

Running this kernel results in:

>> GPU allocation time: 5.827360 ms

>> Host to device transfer time: 23.294975 ms

------- Coalesced warp sgmev kernel ---------

>> Execution time: 2.447360 ms

>> Achieved (GFLOPS): 27.420919

>> Theoretical max (GFLOPS): 1911.040039

>> Maximum memory bandwidth: 112.127998 GB/s

>> Achieves 1.434869 % of peak GFLOPS

>> Achieves 48.927948 % of peak Memory Bandwidth

---------------------------

>> Device to host transfer time: 0.067872 ms

By having coalesced global memory accesses and warp level sum reduction (with block size ) we achieve % of peak memory bandwidth and GFLOPS!

This is closer to cuBLAS but we can do even more.

Kernel 3 - Block-level reductions

In the previous kernel, we had a constraint on the number of threads we can have in one block i.e. for warp level reductions only. In this kernel, in order to have more threads in one block to do more computations we need to perform a block level reduction as well AFTER warp level reduction.

The idea is simple:

Consider there are warps in a block making the total number of threads . Now, let's say we perform a sum reduction on the two warps and store the results of each warp in the first thread of the respective warps.

Thread will store the value of the sum reduction we perform on warp . Similary, thread will store the value of the sum reduction we perform on warp . We now have two values that we need to reduce as summation. Since the values to be reduced are from different warps, this type of reduction is called block level reduction.

Essentially, we will sum the values present in thread and thread , and then store the result in the first memory address of shared memory. Then, only thread can just read the first address in the shared memory and write the final reduced result to the corresponding address in the output vector. The code for this looks like:

extern __shared__ float smem[];

int bid = blockIdx.x;

if (bid >= M) return;

int tid = threadIdx.x;

// each thread calculates its own partial output

float partial_sum = 0.f;

for (int col = tid; col < N; col += blockDim.x) {

partial_sum += matd[bid * N + col] * vecd[col];

}

blockReduceSum(partial_sum, smem, tid, blockDim.x);

// only first thread writes the output to global memory

if (tid == 0) {

float sum = smem[0];

resd[bid] = sum;

}

The utility function blockReduceSum will perform a block-level sum reduction on the partial sums computed by the threads.

Running this kernel results in:

>> GPU allocation time: 5.870848 ms

>> Host to device transfer time: 27.807808 ms

------- Coalesced warp-block sgmev kernel ---------

>> Execution time: 1.607616 ms

>> Achieved (GFLOPS): 41.744339

>> Theoretical max (GFLOPS): 1911.040039

>> Maximum memory bandwidth: 112.127998 GB/s

>> Achieves 2.184378 % of peak GFLOPS

>> Achieves 74.485626 % of peak Memory Bandwidth

---------------------------

>> Device to host transfer time: 0.059232 ms

We are very close to cuBLAS with this kernel now! It achieves % of peak memory bandwidth and GFLOPS.

Can we do more? Let's see :)

Kernel 4 - Vectorized loads

We are already accessing the global memory in a coalesced manner while we are loading the elements of the matrix matd and the vector vecd. But there is something more that we can do, and it is called vectorized loads.

In essence, vectorized loads (and writes) can improve the memory bandwidth performance of our kernel. What this means is: instead of loading the elements matd[i], matd[i + 1], matd[i + 2], and matd[i + 4] in four load instructions, we just load all the floating-point numbers in only one load instruction.

CUDA provides us with a variable type called float4 that can hold floats (x, y, z, and w) i.e. bytes of data considering FP32 precision. To use vectorized loads, we need to cast our corresponding matrix row and input vector as float4 so that the compiler knows that we will be loading these as float4 elements. The code snippet that does this is:

float4* mat_row = reinterpret_cast<float4*>(matd + bid * N);

float4* vec = reinterpret_cast<float4*>(vecd);

Note that we do not recast the entire matrix, we only cast the particular row (which we are working with) of the matrix as float4. Now, when we write something like:

float4 element = vecd[i];

We have access to consecutive floating-point numbers in vecd that can be accessed like:

printf("1st float: %f\n", element.x);

printf("2nd float: %f\n", element.y);

printf("3rd float: %f\n", element.z);

printf("4th float: %f\n", element.w);

To calculate the partial sum now, all we do is:

float4 matval = mat_row[col];

float4 vecval = vec[col];

partial_sum += (matval.x * vecval.x +

matval.y * vecval.y +

matval.z * vecval.z +

matval.w * vecval.w);

One obvious problem to note here is that the number of columns of the matrix (and size of the input vector) must be divisble by to have vectorized loads. But this is solvable if we just "pad" the matrix columns and vector with additional zeros if is not divisible by to not have "out of bounds" memory accesses. We won't be doing that in this kernel for now since we are working with and where both the sizes are divisible by .

Running the vectorized loads kernel results in:

>> GPU allocation time: 5.848320 ms

>> Host to device transfer time: 24.041409 ms

------- Vectorized sgmev kernel ---------

>> Execution time: 1.356800 ms

>> Achieved (GFLOPS): 49.461132

>> Theoretical max (GFLOPS): 1911.040039

>> Maximum memory bandwidth: 112.127998 GB/s

>> Achieves 2.588179 % of peak GFLOPS

>> Achieves 88.254936 % of peak Memory Bandwidth

---------------------------

>> Device to host transfer time: 0.074464 ms

With this kernel, we achieved % of peak memory bandwidth and GFLOPS which performed better than cuBLAS!

We can plot the performance of vectorized loads kernel against cuBLAS for different matrix and vector sizes. Here's what our custom kernel looks like :D

Conclusion

In this worklog, we iteratively optimized the SGEMV operation starting from benchmarking cuBLAS and then writing a custom CUDA kernel for that is comparable to cuBLAS's performance if not better! While cuBLAS achieves GFLOPS and % of the peak memory bandwidth, our custom kernel achieves GFLOPS and % of the peak memory bandwidth.

The full code is available on the GitHub repository: Optimizing SGEMV in CUDA

Also, if you liked reading this blog/worklog then you can follow me on X (formerly Twitter) for real time updates about ML, CUDA, and my life in general.

Thank you for reading!