Learning CUDA by optimizing softmax: A worklog

The softmax operation is crucial. It is used extensively as a layer within deep learning models like transformers where it normalizes raw scores (logits) into a probability distribution. This property makes it particularly useful in classification tasks, where each output neuron represents the likelihood of a specific class. Optimizing softmax, especially in the context of GPU programming with CUDA, presents many opportunities for learning.

In this worklog, we will start by benchmarking PyTorch's softmax operation then finally we will iteratively optimize it in CUDA. The NVIDIA GPU used for this worklog is one GTX 1050Ti (that's all I have got right now).

The full code is available on my GitHub: Optimizing softmax in CUDA

Let's start.

The math

Before getting into it all, let's take a moment to understand the math behind the softmax operation. Softmax for an input vector having elements, produces an output vector with elements, where the element in the output vector is defined as:

Note that softmax operation depends on the current element and also on the sum of exponentials of all the elements of the input vector . We will call this sum as the "normalization factor" (or, norm) henceforth.

Usually, instead of a single vector we deal with a matrix of shape consisting of rows where each row is a vector of elements. Softmax is then performed along the columns of this matrix. The output here will be another matrix of the same shape.

Throughout this worklog, we will be working with a matrix of shape i.e. floating point numbers in total.

Example of the softmax output on a vector containing elements:

import torch

import torch.nn.functional as F

vector = torch.randn(5, dtype=torch.float32)

print("Input vector:", vector)

# softmax along the last dimension

output = F.softmax(vector, dim=-1)

print("Output vector:", output)

Input vector: tensor([-1.3701, 0.7485, 0.1610, -2.0154, 1.0918])

Output vector: tensor([0.0382, 0.3176, 0.1765, 0.0200, 0.4477])

There is a problem though:

If the values of are very large (or very small), then the exponentials might cause overflow or underflow considering the precision limits of floating point numbers on a modern computer. We cannot represent and work with very large or very small numbers. This means for extreme values, the above version of softmax is NOT numerically stable.

But... there is a fix! We can modify the above equation in such a way that the overall operation becomes numerically stable while being correct: We subtract the maximum value of the vector (a constant) from each before computing the exponential. This subtraction operation "shifts" the numbers to a range that can work nicely with floating point numbers. The numerically stable softmax equation becomes:

How this "shifted" equation results in the correct softmax output is left as an excersice to the reader :)

How fast is PyTorch?

We can get a baseline metric on how fast PyTorch is for computing the softmax operation, along the last dimension, on a randomly initialized matrix.

Following the above example, we can get a quick measure for the execution time of the softmax function:

import time

import torch

import torch.nn.functional as F

# Initialize the matrix on devuce

matrix = torch.randn(1024, 32768, device='cuda', dtype=torch.float32)

# Warm up

_ = torch.nn.functional.softmax(matrix, dim=-1)

# Ensure all CUDA operations are finished

torch.cuda.synchronize()

total_time = 0

n_iters = 5

for i in range(n_iters):

# Measure time

torch.cuda.synchronize() # Ensure all CUDA operations are finished

start = time.time()

_ = torch.nn.functional.softmax(matrix, dim=-1)

torch.cuda.synchronize() # Synchronize again

end = time.time()

total_time += (end - start) * 1000

print(total_time)

print(f"Softmax computation time (average): {(total_time/n_iters):.3f} ms")

Softmax computation time (average): 7.226 ms

From our quick test, PyTorch takes around milliseconds to process and compute softmax on the entire matrix. Now, let's see how far can we go with implementing softmax in CUDA.

Kernel 1 - Naive softmax

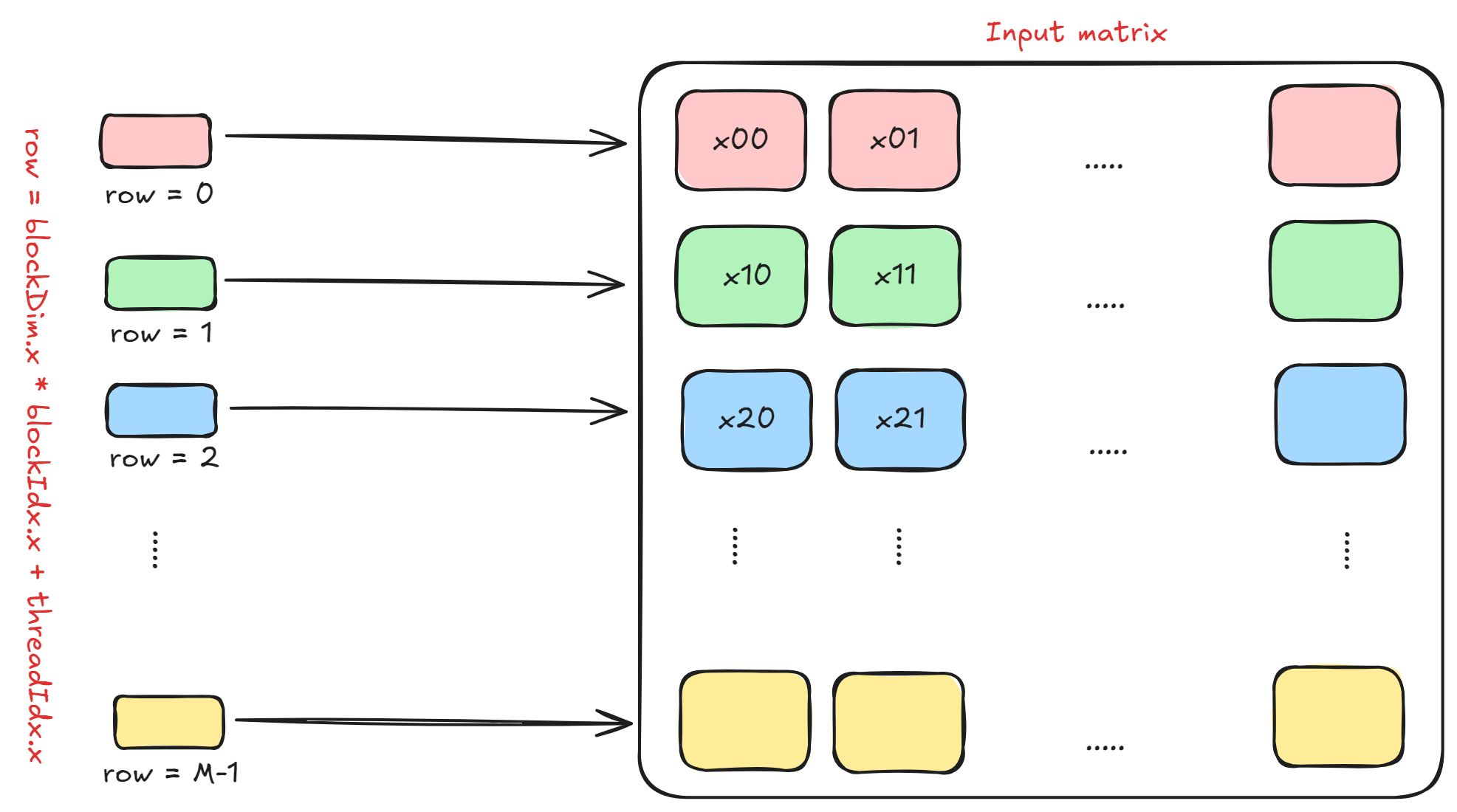

In this kernel, we will assume that each thread in a block processes and computes one entire row of the input matrix. If the number of threads in one block is N_THREADS, then we need a total of ceil(M / N_THREADS) blocks to process the entire matrix.

The figure below shows this. Note that row = blockDim.x * blockIdx.x + threadIdx.x is the row which each thread within some block will process.

The actual computation is quite intuitive here. Softmax is calculated in three passes over the input array:

Pass 1 - Calculation of the maximum: The whole input row is first traversed from left (index = 0) to right (index = N - 1) to find the maximum value .

Pass 2 - Calculation of the norm: The whole input row is traversed from left to right again, but this time the normalization factor is computed using the value from the first pass, for each element.

Pass 3 - Softmax computation: The whole input row is traversed again from left to right and for each element the exponential of is divided by the norm calculated in the second pass.

Below is the specific code snippet that does this:

int row = blockDim.x * blockIdx.x + threadIdx.x;

if (row < M) {

// maximum of this row

float x_max = -INFINITY;

// norm factor of this row

float norm = 0.0f;

// output in 3 passes

for (int col = 0; col < N; col++) {

int i = row * N + col;

x_max = max(x_max, input[i]);

}

for (int col = 0; col < N; col++) {

int i = row * N + col;

norm += expf(input[i] - x_max);

}

for (int col = 0; col < N; col++) {

int i = row * N + col;

output[i] = expf(input[i] - x_max) / norm;

}

}

Running this kernel results in:

>> GPU allocation time: 10.727424 ms

>> Host to device transfer time: 26.176161 ms

>> Kernel execution time: 124.102112 ms

>> Device to host transfer time: 37.320896 ms

The naive kernel takes around milliseconds to execute. This is times slower compared to PyTorch's milliseconds.

Can we improve it? Ofcourse we can.

Kernel 2 - Online softmax

Three passes to compute softmax is not at all optimal. Maybe there's a way to "fuse" the first pass (calculating the maximum) and the second pass (calculating the norm) together.

To do this, we will exploit the multiplication property of exponentials i.e.

To calculate the and norm in just one pass, at each step we need to multiply the "current norm" with a "correction term".

For example, consider the following input vector: for which we need to compute maximum and norm. We will now iterate through this input vector to see what correction term do we need and when do we need it.

Assume that the variables and will represent maximum and norm untill the element.

Starting at :

- We have

- Current element is obviously greater than , so

Note that after the first iteration, the values for maximum and norm are the correct values (but till the first index).

Next at :

- We have

- Current element is less than previous max , so is the maximum after second iteration

We add the "previous norm" value to the "current norm" value at each iteration.

Now at :

- We have

- Current element is greater than previous max , so is the maximum after third iteration.

- We now see that the "global" maximum has changed, rendering the previous norm values to be incorrect.

- What if we multiply to the previous norm in order to correct it? Let's see.

- So, we get

- And then, we simply add the current element's contribution:

- This is the correct global norm! We just corrected it using the property of exponential multiplication followed by the addition of the current element's contribution.

Finally at :

- We have

- Current element is less than previous max , so the global maximum value remains the same i.e.

- Thus,

After the final iteration, we remain with:

and,

We just calculated both maximum and norm factor in only one pass by using a correction term and by exploiting the property of multiplying exponentials! The correction term is:

Now, to write this algorithm as a CUDA kernel, we simply use the naive kernel and "fuse" the first two loops into one:

int row = blockDim.x * blockIdx.x + threadIdx.x;

if (row < M) {

float x_max = -INFINITY;

float norm = 0.0f;

// pass 1

for (int col = 0; col < N; col++) {

int i = row * N + col;

float curr = input[i];

if (curr > x_max) {

// correct the global norm here

norm = norm * expf(x_max - curr);

x_max = curr;

}

norm += expf(curr - x_max);

}

// pass 2

for (int col = 0; col < N; col++) {

int i = row * N + col;

input[i] = expf(input[i] - x_max) / norm;

}

}

Running this kernel results in:

>> GPU allocation time: 10.431488 ms

>> Host to device transfer time: 25.897375 ms

>> Kernel execution time: 88.149567 ms

>> Device to host transfer time: 33.533314 ms

Using this simple trick (also called online softmax) we see that this kernel is times (around %) faster than the naive kernel.

That's a clever improvement, but we can do more. We need to dive deeper into how we can use threads within one block to parallelize the computations even more by collaborating with each other.

Kernel 3 - Shared memory and reductions

The more you learn about GPU programming with CUDA, the more you will realize that memory is structured into hierarchies. The list below shows the access speeds of different memory hierarchies from fastest to slowest.

- Registers (scope is per thread)

- Shared Memory / L1 Cache (scope is per block)

- L2 Cache

- Global Memory (also called, VRAM)

The kernels above uses only global GPU memory. Reading from and writing to global memory is expensive and time consuming, so we need to somehow reduce the access and storing time.

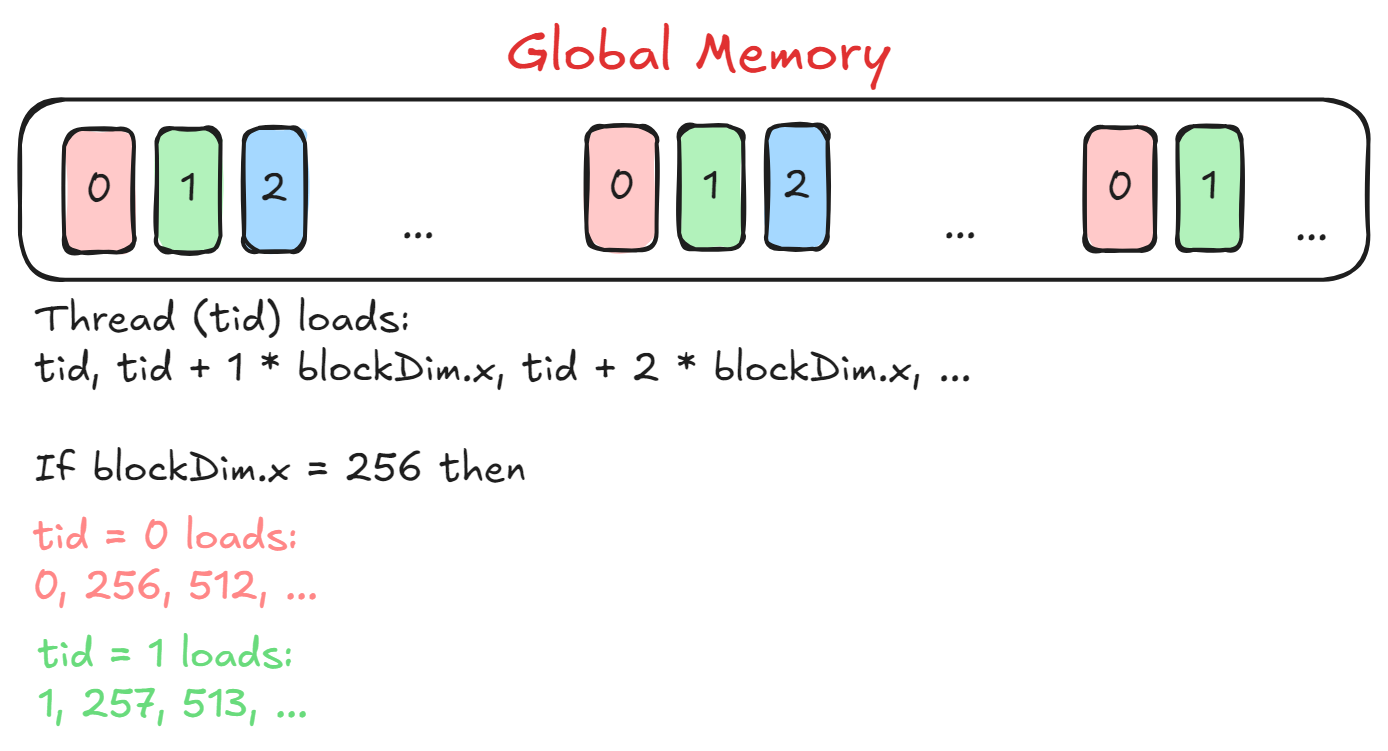

The idea here is to have each block (thread block) process one row of the input matrix and the threads within each block will process only a chunk of the entire row. Have a look at the figure below to understand which elements will each thread load.

Here tid = threadIdx.x loads elements spaced by blockDim.x so that the threads with different tids load consecutive elements from the input row. This helps in achieving memory coalescing where accessing consecutive addresses from the global memory is faster than accessing random addresses.

There is a problem though: To calculate the values of maximum and norm, we need to have access to all the elements of the input row. How will we do that if different threads have access to only a chunk of the input row?

This is where reductions come into play. Bear with me on this one.

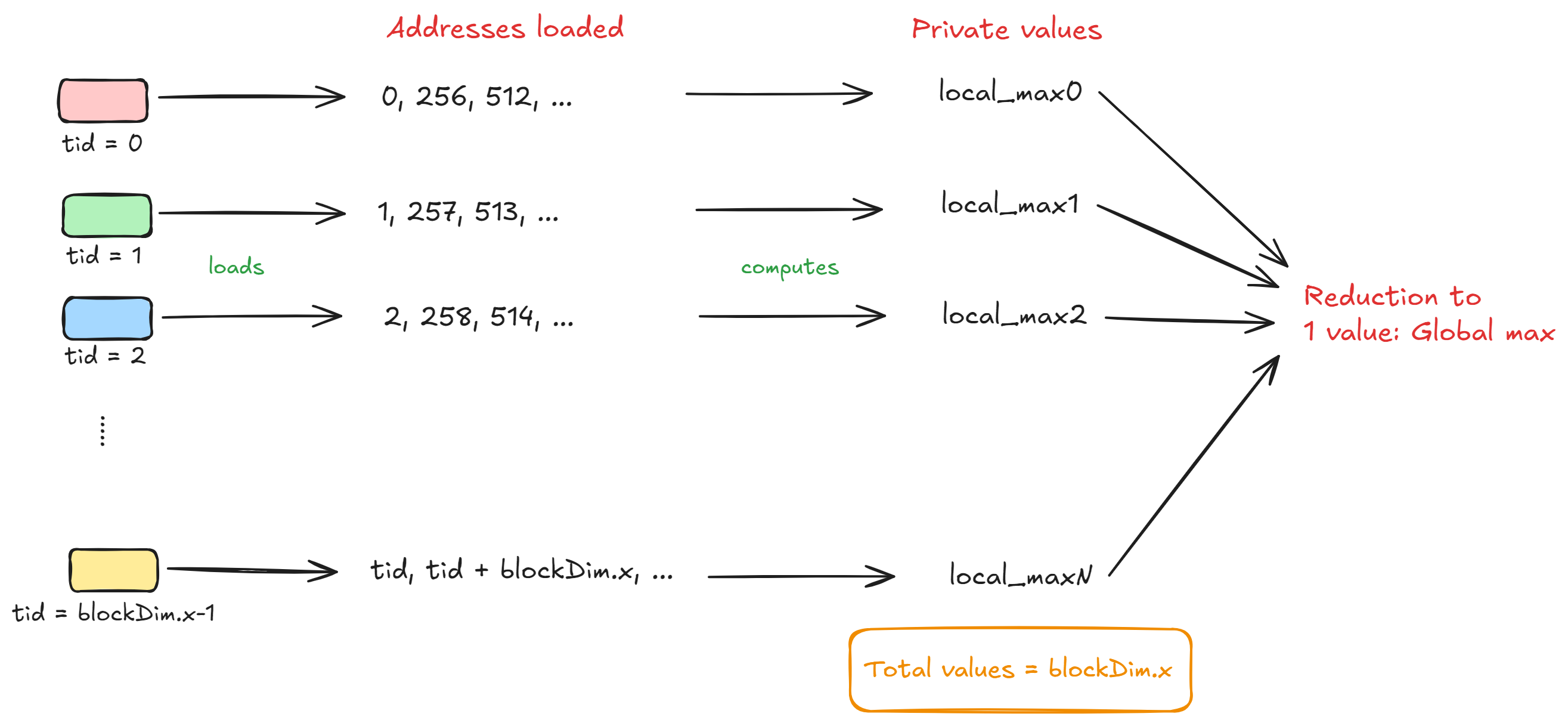

Let's assume each thread has its own private set of variables called local_max and local_norm and also suppose that there are N_THREADS threads in total. Now, the thread with tid = i will compute the local max and local norm using the elements i, i + blockDim.x, i + 2*blockDim.x and so on.

After all the threads in a block complete processing their respective chunks, we will be left with N_THREADS values for local_max and local_norm. To calculate the global maximum value, we need to "reduce" these N_THREADS local maximum values to global maximum value. The figure below will help you understand this.

However, to perform this "block-level" reduction we will need to store the local maximum value in the shared memory of the block. Each thread will store its local maximum as:

smem[tid] = local_max;

__syncthreads();

Note we also add a sync barrier to ensure that each thread correctly stores its local maximum into the corresponding address in the shared memory and waits for other threads before moving on to the reduction step.

We will now use the shared memory to reduce the N_THREADS local maximum values to value and then store it in the first address (smem[0]) in the shared memory. The reduction step looks like:

for (int stride = blockDim.x / 2; stride > 0; stride /= 2) {

if (tid < stride) {

smem[tid] = max(smem[tid], smem[tid + stride]);

}

// sync before next iteration

__syncthreads();

}

float global_max = smem[0];

__syncthreads();

This code block performs reduction in O(log(N)) time complexity which is faster than reducing linearly i.e. O(N) complexity. Let's see an example of this reduction with threads where the shared memory will contain maximum values in the start:

Initially:

smem = [3, 7, 2, 8, 6, 4, 5, 1]

First Iteration (stride = ):

Each thread with tid < 4 compares smem[tid] with smem[tid + stride] and updates smem[tid] with the maximum.

Comparisons:

tid = 0: smem[0] = max(smem[0], smem[4]) = max(3, 6) = 6

tid = 1: smem[1] = max(smem[1], smem[5]) = max(7, 4) = 7

tid = 2: smem[2] = max(smem[2], smem[6]) = max(2, 5) = 5

tid = 3: smem[3] = max(smem[3], smem[7]) = max(8, 1) = 8

Updated smem:

smem = [6, 7, 5, 8, 6, 4, 5, 1]

Second Iteration (stride = ):

Each thread with tid < 2 compares smem[tid] with smem[tid + stride] and updates smem[tid].

Comparisons:

tid = 0: smem[0] = max(smem[0], smem[2]) = max(6, 5) = 6

tid = 1: smem[1] = max(smem[1], smem[3]) = max(7, 8) = 8

Updated smem:

smem = [6, 8, 5, 8, 6, 4, 5, 1]

Third Iteration (stride = ):

Each thread with tid < 1 compares smem[tid] with smem[tid + stride] and updates smem[tid].

Comparison:

tid = 0: smem[0] = max(smem[0], smem[1]) = max(6, 8) = 8

Updated smem:

smem = [8, 8, 5, 8, 6, 4, 5, 1]

Final State:

After the reduction, the maximum value is stored in smem[0], which is:

global_max = smem[0] = 8

This shows how in only iterations, we performed the reduction and got access to the global maximum value from the threads. We do the same reduction for local_norm as well to find the global norm value. The only difference for local norm value is that, instead of performing the max operation we perform the + operation.

Here's how the kernel looks like for reduction of the maximum value:

__shared__ float smem[1024];

int row = blockIdx.x;

int tid = threadIdx.x;

// edge condition (we don't process further)

if (row >= M) return;

float* input_row = xd + row * N;

float* output_row = resd + row * N;

float local_max = -INFINITY;

float local_norm = 0.0f;

for (int i = tid; i < N; i += blockDim.x) {

float x = input_row[i];

if (x > local_max) {

local_norm *= expf(local_max - x);

local_max = x;

}

local_norm += expf(x - local_max);

}

__syncthreads();

smem[tid] = local_max;

__syncthreads();

for (int stride = blockDim.x / 2; stride > 0; stride /= 2) {

if (tid < stride) {

smem[tid] = max(smem[tid], smem[tid + stride]);

}

__syncthreads();

}

float global_max = smem[0];

__syncthreads();

The output from this kernel looks like:

>> GPU allocation time: 10.464928 ms

>> Host to device transfer time: 22.674080 ms

>> Kernel execution time: 6.612160 ms

>> Device to host transfer time: 41.318016 ms

Right away we see that this kernel which uses shared memory and reductions is already around 8.33% (1.09 times) faster than PyTorch's implementation.

Can we improve this even more? Let's see.

Kernel 4 - Shuffle instructions

This kernel will be largely similar to the previous one with one difference. If you notice carefully, in the reduction operations for local maximum value and local norm value we are accessing the shared memory and syncing the threads in every iteration. Even though accessing shared memory is fast, what if we could eliminate the usage of shared memory and syncing barriers while reducing the values?

Before explaining how, we need to understand the concept of warps within thread blocks:

Warps are a fundamental unit of execution within a thread block. A warp is a group of threads in a thread block that execute the same instruction simultaneously (SIMD: Single Instruction, Multiple Data). All threads in a warp execute instructions in lockstep, meaning all threads execute the same instruction at the same time on different data. If a thread block contains threads, the number of warps is

ceil(N / 32). Also, when threads in a warp follow different execution paths (e.g., due to conditional statements), it leads to warp divergence, reducing performance as the threads execute sequentially instead of in parallel.

In our case, if we have blockDim.x = 1024 then each block is composed of warps (each warp consisting of threads).

To limit the usage of shared memory, CUDA provides us with shuffle instructions which are specialized intrinsics that allow threads within a warp to directly exchange data without the overhead of shared memory. These are warp-level primitives and are highly efficient because they use registers to exchange data which is faster than using shared memory (according to the hierarchy).

Suppose in one block we have N_THREADS threads in total. That means, we have NW = ceil(N_THREADS / warp_size) warps where warp_size is usually threads. Now, instead of doing a block-level reduction using shared memory what if we first perform a warp-level reduction:

From N_THREADS values, doing a warp-level reduction for every warp available will leave us with values across the block that needs to be reduced further. So, the first available warp can load the values from the remaining warps, and then perform a warp-level reduction again to get the final value. Let's consider an example to ease your mind:

Suppose there are threads that have already calculated their respective local maximum values. Also, assume that warp_size = 4 which means there are warps in total. The values are [3, 7, 2, 9, 4, 1, 8, 5, 10, 6, 12, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16].

Step 1: Warp-level reduction

The warp size is , so there are warps in the block ( threads / threads per warp). Each warp performs its own reduction.

Warp 0 (Threads 0 to 3: Values [3, 7, 2, 9]):

Offset = :

- Thread 0 compares its value (3) with Thread 2’s value (2): max(3, 2) = 3.

- Thread 1 compares its value (7) with Thread 3’s value (9): max(7, 9) = 9.

Offset = :

- Thread 0 compares its new value (3) with Thread 1’s value (9): max(3, 9) = 9.

Result for Warp 0: 9 (stored in Thread 0 of the warp).

Warp 1 (Threads 4 to 7: Values [4, 1, 8, 5]):

Offset = :

- Thread 4 compares its value (4) with Thread 6’s value (8): max(4, 8) = 8.

- Thread 5 compares its value (1) with Thread 7’s value (5): max(1, 5) = 5.

Offset = :

- Thread 4 compares its new value (8) with Thread 5’s value (5): max(8, 5) = 8.

Result for Warp 1: 8 (stored in Thread 4 of the warp).

Warp 2 (Threads 8 to 11: Values [10, 6, 12, 11]):

Offset = :

- Thread 8 compares its value (10) with Thread 10’s value (12): max(10, 12) = 12.

- Thread 9 compares its value (6) with Thread 11’s value (11): max(6, 11) = 11.

Offset = :

- Thread 8 compares its new value (12) with Thread 9’s value (11): max(12, 11) = 12.

Result for Warp 2: 12 (stored in Thread 8 of the warp).

Warp 3 (Threads 12 to 15: Values [13, 14, 15, 16]):

Offset = :

- Thread 12 compares its value (13) with Thread 14’s value (15): max(13, 15) = 15.

- Thread 13 compares its value (14) with Thread 15’s value (16): max(14, 16) = 16.

Offset = :

- Thread 12 compares its new value (15) with Thread 13’s value (16): max(15, 16) = 16.

Result for Warp 3: 16 (stored in Thread 12 of the warp).

Step 2 - Block-level reduction

At this point, the maximum values from each warp are stored in the first thread of each warp: [9, 8, 12, 16].

The block-level reduction begins.

Store Warp Results in Shared Memory:

- Each warp leader (Thread 0, 4, 8, 12) writes its result to shared memory (smem).

smem = [9, 8, 12, 16].

Synchronize Threads:

- Threads are synchronized using __syncthreads() to ensure shared memory values are visible to all threads.

Perform Final Reduction Using First Warp:

- Only the first warp (Threads 0–3) participates in reducing the values in smem.

First Warp Reduction (smem = [9, 8, 12, 16]):

Offset = :

- Thread 0 compares

smem[0](9) withsmem[2](12): max(9, 12) = 12. - Thread 1 compares

smem[1](8) withsmem[3](16): max(8, 16) = 16.

Offset = :

- Thread 0 compares smem[0] (12) with smem[1] (16): max(12, 16) = 16.

Global Block Maximum: 16 (stored in smem[0]).

At this point, we have the global maximum value for the entire block using warp-level reductions.

How to actually perform these warp-level reductions though? CUDA provides us with shuffle instructions for that. We will use the __shfl_down_sync instruction to perform reduction. Here's how it works:

It is a CUDA warp-level primitive that shifts data values down within a warp. Threads in the warp exchange data based on a specified offset, and threads that would receive data from out-of-bounds threads are assigned a default value. The syntax for __shfl_down_sync is:

T __shfl_down_sync(unsigned mask, T var, int delta, int width=warpSize);

Here:

mask: A bitmask specifying which threads in the warp are active for this operation. We use0xFFFFFFFFto include all threads in the warp.var: The value from the current thread to be shifted.delta: The number of threads to shift the value down.width (optional): The number of threads participating in the operation (must be a power of 2, up to 32). Defaults to the warp size (32).

Consider the following piece of code:

int val = threadIdx.x;

int shifted_val = __shfl_down_sync(0xFFFFFFFF, val, 1);

For delta = 1:

- Thread 0 gets the value of Thread 1.

- Thread 1 gets the value of Thread 2.

- ...

- The last thread in the range gets an undefined value.

The reduction code for this kernel looks like:

float val = local_max;

for (int offset = warp_size / 2; offset > 0; offset /= 2) {

val = fmaxf(val, __shfl_down_sync(0xffffffff, val, offset));

}

if (blockDim.x > warp_size) {

if (tid % warp_size == 0) {

// which warp are we at?

// store the value in its first thread index

smem[tid / warp_size] = val;

}

__syncthreads();

if (tid < warp_size) {

val = (tid < CEIL_DIV(blockDim.x, warp_size)) ? smem[tid] : -INFINITY;

for (int offset = warp_size / 2; offset > 0; offset /= 2) {

val = fmaxf(val, __shfl_down_sync(0xffffffff, val, offset));

}

if (tid == 0) smem[0] = val;

}

} else {

if (tid == 0) smem[0] = val;

}

__syncthreads();

float global_max = smem[0];

__syncthreads();

and the kernel outputs:

>> GPU allocation time: 10.542080 ms

>> Host to device transfer time: 25.580065 ms

>> Kernel execution time: 5.174400 ms

>> Device to host transfer time: 45.923008 ms

This kernel is around times (or, %) faster than the shared memory kernel! Using shuffle instructions eliminated the need of using sync barriers __syncthreads in each iteration as well.

Conclusion

In this worklog, we iteratively optimized the softmax operation starting from PyTorch and then writing a custom CUDA kernel for the same. With the above improvements, our custom softmax CUDA kernel became around times (or, %) faster than PyTorch on RTX 1050Ti.

- The full code is available on my GitHub: Optimizing softmax in CUDA

- Follow me on X (formerly twitter) for real time updates about ML, CUDA, and my life in general: Twitter profile

Thank you for reading!